Your Friend in the Kitchen: FAT TOM

In a restaurant kitchen, or your own, food should be healthful. But it must be safe. Food safety includes protection from physical hazards: Think fish pin bones or tiny shards of metal from a can lid, for example. It also includes concern for chemical hazards: Cleaning supplies don’t belong in the pantry, and we don’t cook in galvanized—zinc-plated—pots and pans. But the concern that gets most of our attention is biological, the things that cause foodborne illnesses or "food poisoning".

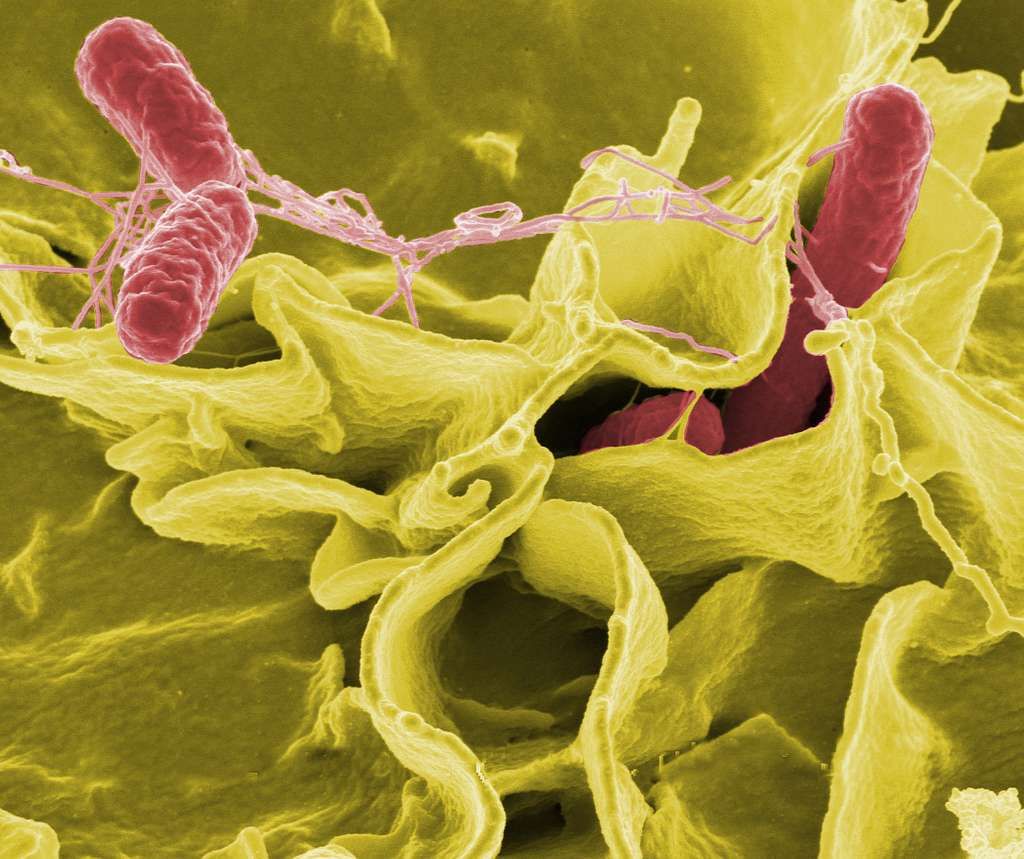

We worry about viruses such as Hepatitis A being transmitted from food handlers to eaters, but dangerous bacteria—pathogens—are the real bad guys, bringing all sorts of fun games to the party: Norovirus, E. coli, ciguatera, salmonella, and bacillus cereus are just a few. What can you do? Wash your hands. Avoid cross-contamination. And learn about FAT TOM. FAT TOM is a mnemonic to help you remember the critical factors in allowing good food to become dangerous: Food, Acidity, Temperature, Time, Oxygen, and Moisture.

Food

Restaurant health inspections pay attention, among other things, to how Potentially Hazardous Foods (PHFs) are handled. Generally speaking, PHFs include meat (and fowl, fish, etc.), eggs, a lot of dairy—notice that these are high-protein foods—cooked food of all sorts, and many prepared raw foods such as cut fruit.

Acidity

Low acidity foods, that is, foods with a neutral or relatively high pH are particularly susceptible to bacteria. High-protein foods are certainly on that list, and so are most cooked foods. Many high-acid foods—think pickles, Tabasco® Sauce, and sauerkraut or Quickle Pickle—are largely immune. Mayonnaise-based salads shouldn’t be left out too long, but because of their relatively high acid content, they’re not as dangerous as the common wisdom might suggest. And while you’ll find that many professional recipes use tomatoes for their acid content, beware: Industrial farming practices have reduced the acidity of the average tomato, and cut tomatoes are now considered to be potentially hazardous.

Temperature

If you keep most foods cold, they will last longer because bacteria grow more slowly or not at all. If you keep them hot enough—such as on a well-run buffet service—bacteria die or can’t grow. PHFs need to be kept below 40°F/4°C or above 140°F/60°C to be safe. The range in between is called the "temperature danger zone". For temperatures up to about 120°F/50°C, figure that every 10°F/5°C above 40°F/4°C roughly doubles the reproductive speed of bacteria.

Incidentally, these temperatures refer to the internal temperature of the foods themselves. Storage, cooking, and holding temperatures drive the internal measurement, but it’s the food the little bugs live in, not the atmosphere around it.

Time

Bacteria are all around us, and it’s a safe assumption that the food on your table is home to some of them. The bad bugs can’t hurt us if we keep their population low enough. But the longer you leave a PHF in the temperature danger zone, or the longer you leave it moist or exposed to oxygen, the longer bacteria have to multiply. Food that has been kept in the temperature danger zone for too long has been "time temperature abused" If a PHF has been so abused—kept for longer than about 2 hours in the temperature danger zone—your safest option is to throw it away.

Oxygen

With some exceptions—botulism-causing bacteria being perhaps the most familiar—foodborne pathogens are aerobic; i.e., they need oxygen to survive and reproduce. That’s why covered food lasts longer and why you should squeeze the air out of (or "burp") your leftovers’ storage containers. It’s also why many meats are now shipped and sold in modified atmosphere packaging (MAP), and why freeze-dried ice cream lasts nearly forever unopened. Oxygen is the culprit when an open bottle of wine starts to taste like vinegar or vegetable oil goes rancid.

Moisture

Without water, there is no life. Generally speaking, moist foods—almost everything on your dinner table, for example—spoil, and dry foods or ingredients (sugar, flour, cornstarch, dried herbs, etc.) do not. Beef jerky is almost entirely protein, but it’s exceptionally resistant to spoilage because it is dry: The heavy application of salt causes osmosis to draw almost all of the water out of the meat, leaving any pathogens dead or inert. Jams and jellies use sugar for the same effect (McGee, "Sugar Preserves"). And dry, aged cheeses such as Parmesan last considerably longer than soft, moist ones such as Brie.

A version of this essay appeared on Analytical Life on 2010-07-21.